The Indirect Costs of Multiple Sclerosis Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Abstruse

Groundwork

Although the economic burden of multiple sclerosis (MS) in high-income countries (HICs) has been extensively studied, data on the costs of MS in low- and middle‐income countries (LMICs) remains scarce. Moreover, no review synthesizing and assessing the costs of MS in LMICs has yet been undertaken.

Objective

Our objective was to systematically identify and review the cost of illness (COI) of MS in LMICs to critically assess the methodologies used, compare price estimates across countries and by level of disease severity, and examine cost drivers.

Methods

Nosotros conducted a systematic literature search for original studies in English, French, and Dutch containing prevalence or incidence-based cost information of MS in LMICs. The search was conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed, Embase (Ovid), Cochrane Library, National Wellness Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Econlit, and CINAHL (EBSCO) on July 2020 without restrictions on publication date. Recommended and validated methods were used for information extraction and analysis to make the results of the COI studies comparable. Costs were adjusted to $US, year 2019 values, using the Earth Bank purchasing ability parity and inflated using the consumer toll alphabetize.

Results

A full of 14 studies were identified, all of which were conducted in upper-middle-income economies. 8 studies used a bottom-up arroyo for costing, and six used a tiptop-downward approach. Four studies used a societal perspective. The total annual price per patient ranged betwixt $US463 and 58,616. Costs varied across studies and countries, mainly because of differences regarding the inclusion of costs of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), the range of cost items included, the methodological choices such as approaches used to estimate healthcare resource consumption, and the inclusion of informal intendance and productivity losses. Characteristics and methodologies of the included studies varied considerably, especially regarding the perspective adopted, cost data specification, and reporting of costs per severity levels. The total costs increased with greater affliction severity. The cost ratios between different levels of MS severity within studies were relatively stable; costs were around i–1.v times higher for moderate versus mild MS and about 2 times higher for severe versus mild MS. MS drug costs were the main cost driver for less severe MS, whereas the proportion of directly non-medical costs and indirect costs increased with greater disease severity.

Decision

MS places a huge economic burden on healthcare systems and societies in LMICs. Methodological differences and substantial variations in terms of absolute costs were plant between studies, which fabricated comparison of studies challenging. Even so, the toll ratios across different levels of MS severity were similar, making comparisons between studies by disease severity feasible. Cost drivers were mainly DMTs and relapse treatments, and this was consistent beyond studies. Nonetheless, the distribution of cost components varied with disease severity.

FormalPara Cardinal Points for Decision Makers

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) imposes a significant economical burden in depression- and middle‐income countries (LMICs). The full costs of the disease increase with affliction severity. Costs of MS drugs dominate in less severe disease, whereas the proportion of straight not-medical costs and indirect costs increases with disease severity. |

| Substantial variations in MS costs were constitute betwixt studies in LMICs, which made comparison of studies challenging. Withal, the cost ratios across different levels of MS severity were similar. Therefore, future cost-of-disease (COI) studies of MS in LMICs should include all MS-related cost categories and study on toll per disease severity level as MS costs significantly depend on Expanded Disability Status Scale categories. |

| COI studies should clearly ascertain the perspective and data sources used. Methodologies adopted to estimate healthcare resources consumption, informal care and productivity losses should be well-defined and in alignment with the country's own healthcare system and specifications every bit a marker of the reliability of the COI estimate. |

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory and demyelinating disease of the fundamental nervous system that affects 2.eight million people worldwide and has a prevalence of 36 per 100,000 people [1]. It is the leading cause of non-traumatic disability in young adults [2] and has an average incidence of ii females for each male [1]. The prevalence of MS varies considerably within regions. San Marino and Germany have the highest prevalence in the world (337 and 303 per 100,000, respectively), followed by the USA (288 per 100,000). Reported MS prevalence rates are considerably lower in low- and middle‐income countries (LMICs) than in high-income countries (HICs), simply these numbers remain uncertain because of the lack of data [1]. For example, the deficient outdated data indicated an estimation of 1.39 per 100,000 in Shanghai in 2004 and of 54.5 per 100,000 in Iran in 2013 [three].

MS is characterized by the loss of motor and sensory functions because of the degeneration of myelin and subsequent loss of the nerves' ability to deport electrical impulses to and from the encephalon [4, 5]. Consequently, MS can cause an array of symptoms, including upper and lower extremity disabilities, visual disturbances, residuum and coordination problems, spasticity, altered sensation, abnormal spoken language, swallowing disorders, fatigue, bladder and bowel problems, sexual dysfunction, and cognitive and emotional disturbances [4, vi, 7]. These symptoms innovate significant disruptions that negatively affect patients' quality of life, interfere with their productivity [8], and place societal costs on healthcare systems, caregivers, patients, and their families [9].

Although the clinical form of the disease is highly variable, MS tin exist categorized into two types based on phenotype: relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and progressive MS. RRMS, which accounts for lxxx–85% of initial diagnoses of MS, is characterized by new or recurrent neurologic symptoms (relapses) and stable periods without disease progression (remissions). Relapses are followed by periods of partial or complete recovery. Progressive MS includes secondary progressive MS, with or without relapses, and principal progressive MS [ten]. MS progression varies from person to person, and the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) is used to measure the degree of impairment in neurologic functions [11]. Available data bespeak that health resources consumption and quality of life differ across EDSS levels [12, thirteen].

Price-of-illness (COI) studies are descriptive analyses assessing the economic burden of a detail health problem over a defined period of fourth dimension [14]. COI studies inform planning of healthcare services, evaluation of policy options, and prioritization of research [fifteen]; they also provide useful information to foster policy fence [xvi]. COI estimates for MS from numerous countries have been published in recent years, reporting substantial costs per patient [17,eighteen,nineteen,twenty]. In line with the increasing number of COI studies and their importance, several literature reviews on the topic highlighted the high economical brunt of MS. Still, these reviews were published earlier 2010 [16, 21,22,23,24], focused on specific geographical areas [25, 26], were restricted to specific treatments or drugs [27, 28], or were limited to one category of costs, such as intangible costs [29] or informal intendance [30]. Systematic reviews published after 2010 included studies from HICs [31,32,33,34,35]. Just one systematic review of MS costs in Latin America, published in 2013 [26], included studies from LMICs, such as Brazil and Colombia. Although the burden of MS in HICs has been extensively assessed, information on the epidemiology and economic burden in LMICs remains scarce [36, 37]. Specifically, exploring the COI of MS in LMICs is urgent, equally the Atlas of MS, third edition [1], showed that MS registries are increasing in these economies, reflecting a high prevalence of MS. Despite this, no previous systematic review has compiled show on the COI of MS in LMICs. Therefore, this study aims to systematically review the evidence on the COI of MS in LMICs to critically assess the methodologies used, compare cost estimates between countries and by level of disease severity, and examine relevant cost drivers.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following the standard methods for conducting and reporting systematic reviews (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] argument) [38]. The protocol of the review was registered a priori with the International Prospective Annals of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42019130059).

Information Search

Nosotros conducted a systematic search of MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed, Embase (Ovid), Cochrane Library, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), EconLit, and CINAHL (EBSCO) to retrieve studies on the COI of MS in LMICs. Records published up to 26 July 2020 were searched without restrictions on publication year. To broaden the sensitivity of our search strategy, both a free-keyword search and controlled vocabulary were used, such as medical subject headings, for each of the databases searched. Three key concepts were considered: multiple sclerosis, cost of illness, AND depression- and middle-income countries. For the latter concept, nosotros used the Cochrane filter 2012 (https://epoc.cochrane.org/lmic-filters) and adapted it to the 2019–2020 World Depository financial institution classification, which categorizes LMICs equally low-income, eye-income, and upper centre-income economies. The search strategy was validated by a medical information specialist. An example of the MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy is bachelor in the electronic supplementary material.

Searching Other Sources

The search was complemented with astern and frontward reference searching. For frontwards reference searching, we searched the Web of Science database for records citing articles that were included in our review. For backward reference searching, nosotros checked the reference lists of included studies.

Eligibility Criteria

We included original studies published in English, French, and Dutch in peer-reviewed journals containing information on prevalence- or incidence-based toll information for developed patients with MS, from LMICs co-ordinate to the 2019–2020 Earth Bank nomenclature [39]. Nosotros excluded editorials, case reports, case serial, reviews, and studies reporting on intangible cost data, children and adolescents, or any type of MS interventions or economic evaluations.

Selection of Studies

Ii reviewers (JD and RR) selected the studies afterward conducting a calibration exercise by testing eligibility conditions to ensure inter-reviewer screening consistency and quality. First, they looked blindly and in parallel for potentially eligible studies past screening the titles and abstracts of the records retrieved by the search. Then, they independently retrieved and evaluated the full texts of references accounted eligible. A screening tool was developed and used for full-text screening. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with other reviewers (MH, IK, and SE).

Data Extraction

Two pairs of authors (JD/RR and JD/IK) independently and in indistinguishable extracted relevant data from the included studies using a data extraction canvass adult by the five authors and pretested using a scale exercise before the actual data extraction. Disagreement between reviewers was solved by discussion among all authors to achieve consensus. We extracted information on the study characteristics, analytical framework (e.g., bottom-up [BU] vs. acme-down [TD] approach), methodology used, well-nigh frequently reported cost categories, total annual cost per patient, and annual cost per patient past severity level and cost ratios.

Data Analysis

The reviewers performed a qualitative synthesis of the data extracted from the included studies. The nature of the data extracted meant a quantitative synthesis was not possible.

It has been reported that the economic brunt of MS includes three cost categories: direct medical, direct non-medical, and indirect. Straight medical costs include inpatient care, outpatient care, drugs, diagnostics, surgical interventions, and doctor services. Straight non-medical costs include home and motorcar modifications, informal intendance provided by family and friends, costs of patients' travel to access healthcare, and most home- and customs-based services. Indirect costs are losses of production due to short- or long-term sickness absence, disability pension, early retirement because of wellness problems, and premature expiry [nine]. Straight medical costs, direct not-medical costs, and indirect costs were reported as included in the studies. The almost frequently reported cost categories in MS COI studies were extracted using a checklist compiled past the authors based on reported MS cost units in previous COI [17,xviii,19] and systematic reviews [31, 34]. The pct of reported cost categories was calculated as a ratio of the most oftentimes reported cost categories in COI studies of MS. Price components across MS severity levels were presented by EDSS categories [11]. EDSS scores range from 0 (= normal neurological functioning) to ten (= decease due to MS). EDSS levels as reported by included studies were classified into three conditions based on EDSS score, with scores of 0–iii indicating mild MS, 4–6.5 indicating moderate, and 7–ix indicating severe. To compare study results and cost components per patient overall and past severity of MS, price estimations per year were converted to $US using World Banking company purchasing power parity [40] and inflated to year 2019 values using the consumer price index [41]. For studies presenting costs for less than 1 year, transformations were made to gauge 1-year costs, assuming no seasonal variations in resources apply. Regarding studies presenting costs for more than than 1 twelvemonth, costs were annualized by bold that costs and healthcare resource consumption were equal during the years of written report. For studies merely presenting total costs per patient by EDSS classification, the weighted yearly boilerplate costs per patient were calculated. When presenting the results, studies were mapped co-ordinate to the method of adding, i.east., BU versus TD approaches, to enhance comparisons between studies using the same methodological approach.

The TD approach relies on population-based data such as registries, and the BU approach estimates costs based on information from individuals with the affliction and may include questions on informal care, transportation, and productivity losses non often found in registries [xvi]. The results of a BU study can start from a subpopulation and be extrapolated to the full population [42].

Dominant toll drivers were determined by identifying the price category with the highest reported cost per study in general and by EDSS level.

Results

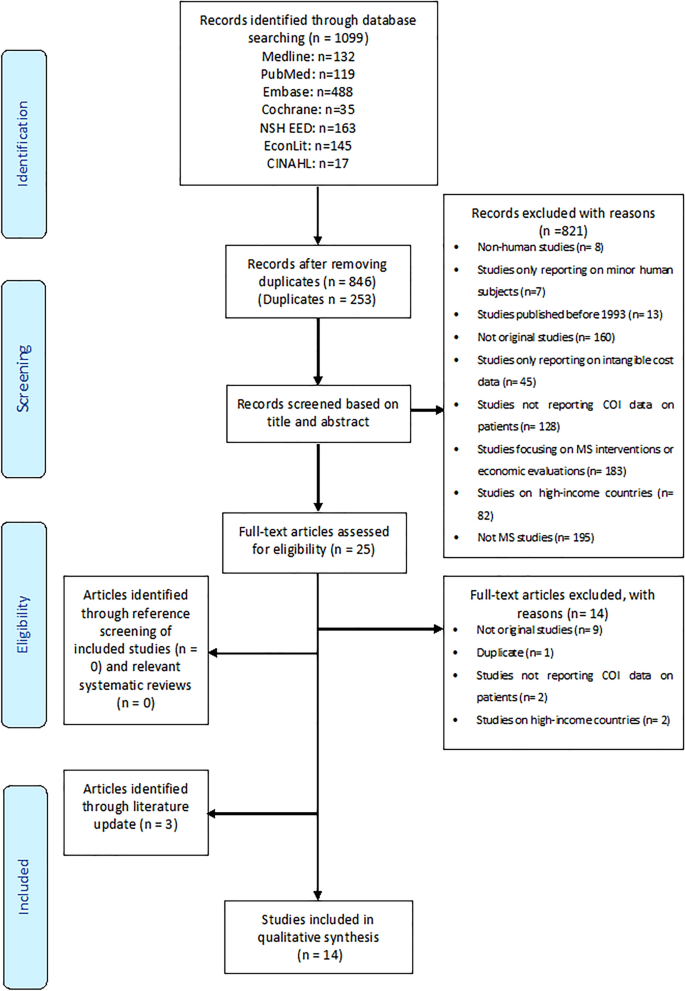

Our initial search, conducted on 5 October 2019, retrieved 1099 records, of which only xi manufactures [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] were deemed eligible. The COI study conducted in Russia was reported in ii articles [13, 47], and we excluded the commodity that presented the results of 16 mostly high-income European countries [thirteen]. The search was rerun in July 2020, resulting in three additional eligible articles [54,55,56] for a total of 14 studies. Figure 1 presents the menses nautical chart detailing the literature search. Backward and frontward reference searching constitute no additional studies. Every bit categorized co-ordinate to the method for calculating costs of MS, 8 of the 14 identified studies used a BU approach [43,44,45,46,47,48, 54, 55], and six used a TD approach [49,50,51,52,53, 56].

PRISMA flowchart of written report selection. COI cost of disease, MS multiple sclerosis

Characteristics of Included Studies

Table i summarizes the characteristics of included studies. They were conducted in 10 countries: six in Latin America (Argentine republic [43], Republic of colombia [50], Mexico [53], and three studies in Brazil [44, 48, 49]), seven in Asia (Turkey [45], Thailand [54], Jordan [51], two studies in Islamic republic of iran [46, 55], and 2 studies in Mainland china [52, 56]), and one in Russia [47]. All included studies were published between 2013 and July 2020 and reported on information nerveless between 2000 and 2018. The number of patients varied from vii in the report by McKenzie et al. [51] to 23,082 in the study by Maia Diniz et al. [49] from Brazil. The mean historic period of patients ranged between 33.5 [46] and 46.i years [56]. The percentage of females included varied between 57.0% [51] and 78.7% [44]. The definition of MS was according to the RRMS definition [53], a combination of RRMS, secondary progressive MS, primary progressive MS [44,45,46,47,48], or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [43, 49,l,51,52, 54, 56]. One study [55] did non report a definition of MS. All eight BU [43,44,45,46,47,48, 54, 55] studies reported information and costs per patient according to disease severity using the EDSS classification. Only Chanatittarat et al. [54] used a different EDSS nomenclature (0–2.five, 3–5.5, 6–7.5, 8–ix.5). Enrollment of patients in all BU studies were up to 1 year, and the timeframe for TD studies varied between 2 and sixteen years.

Study Methodologies

Report methodologies and costs per patient are presented in Table two. One BU report [46] did not conspicuously land whether costs were estimated prospectively or retrospectively; all other BU studies were clearly retrospective and reported prevalence-based COI estimates. Four BU studies used the societal perspective [43, 44, 47, 54], ane [48] used a household and healthcare system perspective, one [55] used a household perspective, and two [45, 46] did not report the perspective of the analysis. All BU studies measured costs based on a questionnaire. Most BU studies used multiple data sources; two [54, 55] did not written report their information sources for costs. Of all BU studies using the human being upper-case letter approach to calculate productivity losses, only da Silva et al. [48] described the impact of productivity losses on patients with MS without converting them into monetary values. Most of the BU studies used opportunity costs to summate informal care costs [43,44,45,46,47], whereas the study from Islamic republic of iran [55] did non clearly study the adding method for costing breezy care.

Five of the TD studies reported prevalence-based COI estimates and were retrospective; Macías-Islas et al. [53] was the exception. 3 TD studies [49, 50, 53] used multiple perspectives, 2 studies [51, 52] did not report the perspective of the analysis, and the perspective used by Du et al. [56] was unclear. TD studies used different cost measurement tools, i.east., patient records, clinical records, claims, and/or health insurance coverage. Some used a single toll listing source, and others used a combination of data sources. The study from China past Du et al. [56] did not report any data sources for costs.

Toll Categories

Table 3 presents the detailed cost categories reported in 13 studies according to the three classifications: direct medical, direct non-medical, and indirect costs. One study [51] did not report any cost category and so was non included in this table. All simply 1 [fifty] of the 13 studies explicitly reported straight costs for inpatient and outpatient intendance. All studies reported straight medical costs and, explicitly, the costs of drugs and medical investigations.

All studies reported different costs of healthcare consultation subcategories. Only three studies [43, 47, 48] explicitly reported on all four drug subcategories. In the 13 studies included in Table 3, illness-modifying therapies (DMTs) were the well-nigh used drug subcategories, followed by other prescribed medications, and relapse treatments. All except 2 studies [52, 53] included direct not-medical costs. Five BU studies [43,44,45, 54, 55] included costs of formal care, informal intendance, and investments and equipment, whereas TD studies did not include any costs for formal and breezy care. All except one [48] BU report reported indirect costs, whereas TD studies did not. 4 studies [43,44,45, 55] reported explicitly on productivity losses and absenteeism. Ii studies [44, 47] specifically reported costs of short-term absences, long-term absences, and early retirement. Four BU studies [44, 45, 47, 48] assessed MS disease symptoms and health-related quality of life but did not catechumen them into monetary values.

The types of cost items included varied between the BU studies, whereas TD studies included fewer categories for cost specifications. The largest percentage (88%) of included cost categories was reported in the BU study from Russia [47], and the smallest pct (13%) was included in the TD report from China [52]. For example, amidst BU studies, the written report from Iran [46] had few specified cost categories compared with the high number of cost categories included in the studies from Brazil [44, 48] and Turkey [45]. Even though the number of cost categories reported by Imani et al. [55] was double that reported in the other study from Iran [46], both studies reported similar annual costs per patient.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Costs

The total costs per patient with MS ranged betwixt $US463 [52] and 58,616 [43] (year 2019 values). Among BU studies, the annual costs per patient were up to ix times higher, with an average cost per patient of $US58,616 in Ysrraelit et al. [43] compared with $US6247 in Torabipour et al. [46]. The average per centum of directly and indirect costs in BU studies was 89 and 11% of the full costs, respectively. The per centum of direct costs varied betwixt 78% [47, 54] and 100% [48] of the full costs, and the highest per centum of indirect costs was 22% for the studies in Russia [47] and Thailand [54].

Comparing of the studies using the societal perspective showed costs per patient were up to three times higher: $US58,616 for Ysrraelit et al. [43] compared with $US15,540 for Kobelt et al. [44].

The two studies from Brazil [44, 48] presented dissimilar average costs per patient: the report using a societal perspective and including indirect costs presented more than than 40% lower average costs.

The annual costs per patient in TD studies ranged from $US463 for Min et al. [52] to $US41,514 for Macías-Islas et al. [53].

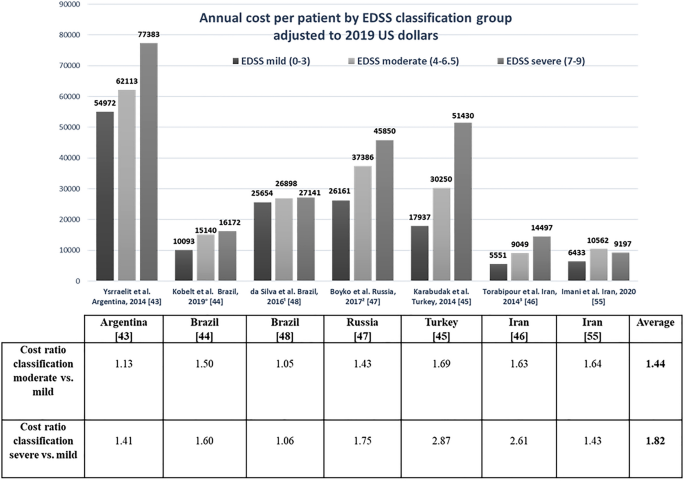

Cost per Patient past Expanded Disability Condition Scale Nomenclature Group

Effigy 2 presents the almanac price per patient past EDSS nomenclature group, adjusted to yr 2019 $US, and cost ratios by illness severity for BU studies [43,44,45,46,47,48, 55]; ane study [54] that did not present costs per EDSS level was excluded. Results of six studies showed that costs per patient increased with disease severity. The highest price ratio was reported in the study from Turkey [45]: 1.69 for moderate versus mild disease and 2.87 for severe versus balmy disease. The smallest variation betwixt disease classed every bit moderate versus mild and severe versus mild was reported in the written report from Brazil [48], with ratios of i.05 and 1.06, respectively. The calculated mean price ratios in BU studies for disease classed every bit severe versus mild (1.82) was 26.5% college than the mean ratio for moderate versus mild affliction (i.44). All cost ratios for severe versus mild disease were college than for moderate versus balmy, except for the study from Islamic republic of iran by Imani et al. [55], in which costs for moderate disease were higher than for severe disease. The range of the price ratios for astringent versus mild illness (1.81) was college than that for moderate versus mild affliction (0.64). Costs per patient by EDSS classification varied widely betwixt BU studies, with the widest variation amidst cost per patient by astringent EDSS group, where the highest price was $US77,383 [43] compared with $US9197 [55], the lowest price for the same classification. However, the cost ratios for severe compared with moderate affliction for the same studies were almost the same at one.41 [43] and one.43 [55].

Almanac cost per patient past Expanded Disability Condition Scale (EDSS) classification group adjusted to $US, year 2019 values, and cost ratios for lesser-upwardly studies. Note that Chanatittarat et al. [54] did not report any cost by EDSS classification. °Data courtesy of Prof. Gisela Kobelt [44] via personal communication. oneData about EDSS level was unavailable for two patients in da Silva et al. [48]. iiEDSS data was missing for twenty patients in Boyko et al. [47]. 3To obtain the price per patient per year for the report by Torabipour et al. [46] from Iran, we annualized resources used by assuming that nerveless data on resources were representative of patient utilize over the whole year

Price Drivers

Cost drivers differed among included studies [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,l,51,52,53,54,55,56], based on the different levels of cost data specification. Amidst BU studies, DMTs and relapse treatments were the main cost drivers among studies in the mild EDSS group. Although the cost drivers varied more betwixt studies in the moderate EDSS group, relapse treatments and DMTs remained the most dominant cost driver [43, 45, 47, 48, 54, 55], followed by out-of-pocket expenses [44] and home care costs [46]. However, the price drivers varied widely betwixt studies in the severe EDSS group, where the drivers across studies included relapse treatments and DMTs [43, 48, 55], informal and formal care [45], rehabilitation [46], and indirect costs [44, 47]. The economic brunt increased with greater physical disability, equally the toll drivers for severe patients shifted from straight costs to indirect costs. In the TD studies [50,51,52,53, 56], direct medical costs were the dominant cost drivers; these studies did non include indirect costs.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 14 studies investigating the cost of MS in LMICs. All included studies were conducted in upper-center-income economies, highlighting the absence of COI studies of MS in low-income and depression-eye-income economies. Furthermore, no studies were conducted in Africa. All studies were published between 2013 and 2020 and reported on data collected between 2000 and 2018, suggesting that COI studies of MS are a topic of recent and increasing interest in LMICs. The annual costs of patients with MS differed greatly amidst COI studies in LMICs, ranging betwixt $US463 [52] and 58,616 [43] (year 2019 purchasing power parity values). This could exist explained by large methodological variations between the identified studies, and both costs and toll drivers appeared to be influenced by methodological choices. This MS cost variation could likewise be attributed to the significant heterogeneity across LMICs, which creates differences in resource use. Furthermore, our study suggested that the total costs increased with disease severity. DMTs and relapse treatments were the main price drivers for MS in general beyond studies, but price drivers varied widely beyond severity levels. Costs of MS drugs were the major price driver in lower severity levels, whereas the proportion of direct non-medical costs and indirect costs increased with disease severity.

Methodological and Contextual Differences for Comparability Between Studies

Overall, higher costs per patient were reported in Latin American countries [43, 44, 48,49,fifty, 53], Turkey [45], Russia [47], and Thailand [54], whereas lower costs were constitute in Iran [46, 55], China [52, 56], and Jordan [51]. Specifically, for the first set of countries, the annual costs per patient ranged from $US15,540 (average cost) in Kobelt et al. [44] to $US58,616 in Ysrraelit et al. [43], and the inclusion of DMTs accounted for xl–99% of the average total toll per patient, except for the study in Thailand [54], which did not specify the types and percentage of DMTs included. The studies that did non explicitly include DMTs [46, 51, 52, 56] reported lower annual costs per patient, ranging from $US463 (boilerplate cost) in China [52] to $US9523 in Hashemite kingdom of jordan [46]. Although the study in Islamic republic of iran by Imani et al. [55] included costs of DMTs, the depression cost per patient ($US7476) could exist attributed to the use of the household perspective. Amongst the 3 studies [43, 44, 47] that used a societal perspective, a BU approach, and a relatively common methodology to estimate the COI, the accented costs per patient varied co-ordinate to the proportion of those costs that were estimated to be DMT costs. For case, DMTs accounted for 87.9% of the total costs per patient ($US58,616) in Argentina [43], 57.ane% in Russian federation ($US30,358) [47], and 40.3% in Brazil ($US15,556) [44]. Although the three studies in Brazil [44, 48, 49] used different methodologies, the full costs per patient increased equally the percentage of full costs attributable to DMTs increased. These findings suggest a positive clan between the inclusion of DMTs and the total costs per patient. Straight medical costs, inclusive of DMTs, corresponded to the greatest proportion of the total costs across the 14 included studies. Price drivers were mainly DMTs and relapse treatments and were stable beyond studies. Yet, the distribution of cost components varied with severity level. MS drug costs dominated in the mild and moderate EDSS groups, whereas relapse treatments, rehabilitation, indirect costs, and informal care were the cost drivers across studies in the severe EDSS group.

Although absolute costs differed between studies, it appears that the toll ratios between different severity levels across included studies were relatively stable at approximately ane–1.5 between EDSS balmy and moderate classifications, and two between EDSS mild and severe.

Similar to the results of previous systematic reviews of the COI of MS in HICs [23, 24, 31, 34, 35], our findings in LMICs confirm that costs increase with level of disability, as the proportion of direct non-medical costs and indirect costs increased with disease severity. Nonetheless, in LMICs, indirect costs representing productivity losses appear low and less dominant in the most astringent group compared with studies from HICs, where indirect costs represented the bulk of the costs. This is primarily because of the distribution of the sample across severity levels. The BU studies included a larger percentage with early disease, representing a larger proportion remaining in the work force [43,44,45,46,47,48, 55] (the mild EDSS grouping accounted for 40–85% of the samples in included studies). This is in comparison with the findings of Ernstsson et al. [31] in HICs, where the mild EDSS group accounted for 21.3–47.7% of the samples in included studies. Moreover, the proportion of informal work and shadow economies in developing countries [57, 58], as well as the method used to assess productivity losses, might take a considerable effect on the costs.

Several important methodological aspects of COI studies are essential to consider in systematic reviews. These include the perspective of the analysis, the scope of costs measured, the analytical framework used to approximate costs (BU vs. TD arroyo), and the arroyo used i.e., prevalence- or incidence-based approach [59]. Recent systematic reviews of COI studies of MS in HICs [31, 35] included comparable study characteristics and used methodologies with but minor differences. The majority of COI studies in HICs adopted a societal perspective, primarily a BU approach, and a cross-exclusive retrospective analysis and included different levels of direct and indirect cost data specifications. This enabled systematic reviews [31, 35] to conduct a descriptive analysis for studies that reported costs by disease severity (balmy, moderate, and severe). The majority of COI studies in HICs are in alignment with local and international wellness economic guidelines [17, 59,60,61] for conducting and reporting COI studies. However, in our systematic review, the characteristics of, and the methodologies used in, the included studies were highly heterogeneous, specially regarding the perspective adopted, price data specification, and reporting of costs per severity levels. For case, only seven [43,44,45,46,47,48, 55] of the 14 studies presented indirect costs per patient as well equally costs per severity level. Thus, detailed and unambiguous reporting of cost units is of import as it enables comparing of methodologies and outcomes of COI studies.

The country-related contexts vary widely in the three different economical groups (low, middle, and upper-middle income) in LMICs. The high heterogeneity across these countries probable affects the costs of MS because of several country-related factors, including healthcare context-specific issues [62], assessment of healthcare resource consumption, informal care and productivity losses [xxx, 60, 63], reimbursement policies [64], and other cultural and socioeconomic aspects [65]. For instance, transportation costs were higher in the studies from Iran [46, 55] because they were conducted in provinces far outside the capital where MS centers are located. Furthermore, informal care costs and productivity losses were less ascendant in studies from Iran [46, 55] than in those from Argentina [43], Brazil [44], and Russia [47], where formal labor force participation is more prevalent. Cultural aspects may lead to underestimations of informal care; this could exist the case in countries such as Islamic republic of iran where women do not play a significant role in the formal labor market. Furthermore, the definition of informal care could be perceived differently betwixt countries, which will influence the comparability of these studies [thirty, lx, 63]. Luz et al. [62] institute that the lack of quality local clinical data is an important technical and context-specific issue when conducting wellness economic evaluations in LMICs. Thus, this heterogeneity necessitates that methodologies adopted to estimate healthcare resource consumption, breezy care, and productivity losses should be well-divers and in alignment with the country's own healthcare system and specifications every bit a marker of the reliability of the COI gauge.

Contextual differences among countries may lead to large differences in costs per patient [23] and complicate the transferability of economic data across jurisdictions [66,67,68]. Brodszky et al. [69] showed that COI studies in European HICs and upper-heart-income economies provided country-specific results, thus limiting the transferability of results. The findings of studies included in this systematic review derived only from upper-eye-income countries, potentially rendering data non-transferable to low-income and low-middle-income economies, where significant variations exist among these groups.

Despite the heterogeneity of the studies included in this systematic review, we used several methodologies to present our findings. Mapping studies according to their method of adding (BU vs. TD) and using purchasing power parity to convert cost estimates of different currencies to year 2019 $Usa enhanced the comparability of these studies.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths and limitations of this review should be considered. Nosotros used a highly sensitive search strategy that probable discovered all relevant literature, followed the PRISMA guidelines [38], and registered the report protocol with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. Although the burden of MS in HICs has been extensively assessed, to our knowledge, this study represents the outset systematic review compiling show most MS in LMICs. Moreover, nosotros strived to raise the comparability of the results of the included studies despite their heterogeneity by using recommended and validated methods such as adjusting costs to $US, twelvemonth 2019 values, using World Bank purchasing ability parity [forty] and inflating using the consumer toll index [41]; mapping studies according to the method of calculation (BU vs. TD); and computing yearly costs per patient for some studies.

Yet, at that place are as well some limitations to this study. Kickoff, performing a quality assessment of included COI studies was impossible in the absence of a quality assessment checklist. Larg and Moss [15] published a guide to critical evaluation for COI studies only did not provide a value judgment for each criterion. Therefore, no formal quality assessment of COI studies was conducted using a formal checklist; rather, guidance about the main elements of methodologies that should be considered in COI studies of MS in LMICs was provided in the discussion of this paper. Second, this review was restricted to original studies published in English, French, and Dutch. Consequently, one study [37] in Spanish was excluded, and it is possible that other COI studies of MS in dissimilar languages could have been missed. Finally, the literature search did not encompass governmental reports.

Time to come Directions

Variations between countries precluded extrapolation of information on the COI of MS, and comparisons of costs in absolute terms were unfeasible. Thus, establishing a guideline for conducting and reporting COI studies of MS in LMICs to amend their consistency, reliability, and transferability is needed. Future COI studies of MS in LMICs should include all MS-related cost categories, calculate cost per severity level as MS costs are highly significantly dependent on EDSS categories, and clearly define the data source and methodology adopted in alignment with the country's own healthcare system and specifications. Future MS COI studies and systematic reviews should likewise pay more attention to low-income, and low-centre-income countries. In add-on, there is a full general demand to develop a consensus quality cess for COI studies with guideline-based interpretations to make the scoring feasible.

Conclusion

Despite the heterogeneity of studies identified, this systematic review provided a general characterization of the huge economical burden and main cost drivers of MS in LMICs. Toll drivers were mainly DMTs and relapse treatments and were broadly stable across studies. Withal, our findings support that the distribution of cost components varied with the level of illness severity. MS drug costs dominated in lower severity levels, whereas the proportion of direct non-medical costs and indirect costs increased with illness severity. As expected, total costs increased with greater disease severity. Our findings also provide strong back up for the concern that there are methodological differences and great variations in term of accented costs per patient across studies and countries, making comparison challenging. However, the cost ratios across different levels of MS severity were similar, making comparisons between studies viable. This report provided basic and contextual recommendations for future researchers on methodological considerations for studies of the COI of MS in LMICs.

References

-

The Multiple Sclerosis International Federation, Atlas of MS, tertiary Edition (September 2020).

-

Dua T, Rompani P, Globe Health Organization, Multiple Sclerosis International Federation, editors. Atlas: multiple sclerosis resource in the world, 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2008.

-

Eskandarieh Due south, Heydarpour P, Minagar A, Pourmand S, Sahraian MA. Multiple sclerosis epidemiology in East Asia, Southward Eastern asia and Southern asia: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;46:209–21.

-

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:xvi.

-

Karussis D. The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and the various related demyelinating syndromes: a critical review. J Autoimmun. 2014;48–49:134–42.

-

Noseworthy JH, Rodriguez Grand, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. Northward Engl J Med. 2000;xv:938–52.

-

Zindler East, Zipp F. Neuronal injury in chronic CNS inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2010;24:551–62.

-

Judicibus MAD, McCabe MP. The impact of the financial costs of multiple sclerosis on quality of life. Int J Behav Med. 2007;14:3–eleven.

-

Trisolini M, Honeycutt A, Wiener J, Lesesne S. RTI International 3040 Cornwallis Road Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 USA: 104.

-

Vollmer T. The natural history of relapses in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256:S5-13.

-

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic damage in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1444.

-

Kobelt G. Costs and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:918–26.

-

Kobelt M, et al. New insights into the brunt and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler J. 2017;23:1123–36.

-

Rice DP. Estimating the price of illness. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1967;57:424–40.

-

Larg A, Moss JR. Cost-of-illness studies: a guide to critical evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29:653–71.

-

Tarricone R. Cost-of-disease assay. Wellness Policy. 2006;77:51–63.

-

Svendsen B, Myhr Thou-Thou, Nyland H, Aarseth JH. The cost of multiple sclerosis in Norway. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13:81–91.

-

Karampampa Yard, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, Eckert B. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS report: results from five European countries. Mult Scler. 2012;eighteen:7–15.

-

Palmer AJ, Colman S, O'Leary B, Taylor BV, Simmons RD. The economic impact of multiple sclerosis in Australia in 2010. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1640–6.

-

Reese JP, John A, Wienemann One thousand, Wellek A, Sommer North, Tackenberg B, et al. Economic burden in a German cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2011;66:311–21.

-

Grudzinski AN, Hakim Z, Cox ER, Bootman JL. The economics of multiple sclerosis: distribution of costs and relationship to disease severity. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15:229–twoscore.

-

Kobelt G. Economical show in multiple sclerosis: a review. Eur J Health Econ. 2004;five:s54-62.

-

Patwardhan MB, Matchar DB, Samsa GP, McCrory DC, Williams RG, Li TT. Cost of multiple sclerosis by level of disability: a review of literature. Mult Scler. 2005;11:232–nine.

-

Orlewska E. Economic brunt of multiple sclerosis: what can nosotros learn from toll-of-disease studies? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2006;6:145–54.

-

Adelman G, Rane SG, Villa KF. The cost burden of multiple sclerosis in the U.s.: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Econ. 2013;16:639–47.

-

Romano M, Machnicki Thou, Rojas JI, Frider N, Correale J. In that location is much to exist learnt nearly the costs of multiple sclerosis in Latin America. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2013;71:549–55.

-

Sharac J, McCrone P, Sabes-Figuera R. Pharmacoeconomic considerations in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Drugs. 2010;70:1677–91.

-

Phillips CJ. The cost of multiple sclerosis and the price effectiveness of disease-modifying agents in its handling. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:561–74.

-

Wundes A, Brown T, Bienen EJ, Coleman CI. Contribution of intangible costs to the economic brunt of multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ. 2010;13:626–32.

-

Oliva-Moreno J, Trapero-Bertran One thousand, Peña-Longobardo LM, del Pozo-Rubio R. The valuation of breezy intendance in cost-of-affliction studies: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:331–45.

-

Ernstsson O, Gyllensten H, Alexanderson K, Tinghög P, Friberg Eastward, Norlund A. Cost of affliction of multiple sclerosis—a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;eleven:e0159129.

-

Karampampa G, Gustavsson A, van Munster EThL, Hupperts RMM, Sanders EACM, Mostert J, et al. Handling experience, burden, and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in multiple sclerosis study: the costs and utilities of MS patients in The Netherlands. J Med Econ. 2013;sixteen:939–l.

-

Kolasa K. How much is the cost of multiple sclerosis–systematic literature review. Przegl Epidemiol. 2013;67(1):75.

-

Naci H, Fleurence R, Birt J, Duhig A. Economic Burden of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:363–79.

-

Paz-Zulueta One thousand, Parás-Bravo P, Cantarero-Prieto D, Blázquez-Fernández C, Oterino-Durán A. A literature review of cost-of-illness studies on the economical burden of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;43:102162.

-

Risco J, Maldonado H, Luna L, Osada J, Ruiz P, Juarez A, et al. Latitudinal prevalence gradient of multiple sclerosis in Latin America. Mult Scler. 2011;17:1055–nine.

-

Romero Grand, Arango C, Alvis North, Suarez JC, Duque A. Costos de la Esclerosis Múltiple en Colombia. Value in Wellness. 2011;xiv:S48-50.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Grouping. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pmed.1000097.

-

World Banking company State and Lending Groups. 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-state-and-lending-groups. Accessed Apr 2020.

-

PPP conversion cistron, Gross domestic product (LCU per international $). 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP. Accessed Apr 2020.

-

Inflation Calculator. 2020. https://cpiinflationcalculator.com/ Accessed Apr 2020.

-

Henriksson F, Jönsson B. The economic price of multiple sclerosis in Sweden in 1994. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;xiii:597–606.

-

Ysrraelit C, Caceres F, Villa A, Marcilla MP, Blanche J, Burgos M, et al. ENCOMS: Argentinian survey in cost of illness and unmet needs in multiple sclerosis. Arq Neuro Psiquiatr. 2014;72:337–43.

-

Kobelt G, Teich V, Cavalcanti Grand, Canzonieri AM. Burden and toll of multiple sclerosis in Brazil. PLoS One. 2019;fourteen:e0208837.

-

Karabudak R, Karampampa M, Çalışkan Z, on behalf of the TRIBUNE Written report Grouping. Handling experience, brunt and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from Turkey. J Med Econ. 2015;18:69–75.

-

Torabipour A, Asl ZA, Majdinasab North, Ghasemzadeh R, Tabesh H, Arab M. A study on the direct and indirect costs of multiple sclerosis based on expanded disability status scale score in Khuzestan, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:8.

-

Boyko A, Kobelt 1000, Berg J, Boyko O, Popova E, Capsa D, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: Results for Russia. Mult Scler. 2017;23:155–65.

-

da Silva NL, Takemoto MLS, Damasceno A, Fragoso YD, Finkelsztejn A, Becker J, et al. Cost analysis of multiple sclerosis in Brazil: a cross-sectional multicenter study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:102.

-

Maia DI, Guerra AA, de Lemos LLP, Souza KM, Godman B, Bennie Yard, et al. The long-term costs for treating multiple sclerosis in a xvi-year retrospective cohort study in Brazil. PLoS One. 2018;xiii:e0199446.

-

Muñoz-Galindo IM, Moreno Calderón JA, Guarín Téllez NE, Arévalo Roa HO, Díaz Rojas JA. Wellness intendance cost for multiple sclerosis: the case of a Wellness Insurer in Republic of colombia. Value Health Reg Bug. 2018;17:xiv–20.

-

McKenzie ED, Spiegel P, Khalifa A, Mateen FJ. Neuropsychiatric disorders among Syrian and Iraqi refugees in Jordan: a retrospective cohort written report 2012–2013. Confl Health. 2015;9:x.

-

Min R, Zhang X, Fang P, Wang B, Wang H. Health service security of patients with 8 certain rare diseases: evidence from Communist china'south national organisation for wellness service utilization of patients with healthcare insurance. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:204.

-

Macías-Islas MA, Soria-Cedillo IF, Velazquez-Quintana M, Rivera VM, Baca-Muro VI, Lemus-Carmona EA, et al. Cost of care according to illness-modifying therapy in Mexicans with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:415–xx.

-

Chanatittarat C, Chaikledkaew U, Prayoonwiwat N, Siritho Southward, Pasogpakdee P, Apiwattanakul M, et al. Economic brunt of Thai patients with inflammatory demyelinating central nervous system disorders (IDCD. Pharm Sci Asia. 2019;46:260–9.

-

Imani A, Gharibi F, Khezri A, Joudyian Northward, Dalal Chiliad. Economical costs incurred by the patients with multiple sclerosis at different levels of the disease: a cross-sectional study in Northwest Iran. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:205.

-

Du Y, Min R, Zhang 10, Fang P. Factors associated with the healthcare expenditures of patients with multiple sclerosis in urban areas of China estimated past a generalized estimating equation. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;21:137–44.

-

Schneider F, Buehn A, Montenegro CE. Shadow economies all over the world: New estimates for 162 countries from 1999 to 2007. World Bank policy research working newspaper. 2010 (5356).

-

Schneider F, Klinglmair R. Shadow economies around the world: What do we know? 2004. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=518526. Accessed 15 July 2020.

-

Hodgson TA, Meiners MR. Cost-of-Affliction methodology: a guide to current practices and procedures. Milbank Meml Fund Q Health Soc. 1982;lx:429.

-

Clabaugh K, Ward MM. Cost-of-illness studies in the U.s.a.: a systematic review of methodologies used for direct cost. Value Wellness. 2008;11:13–21.

-

Akobundu E, Ju J, Blatt L, Mullins CD. Cost-of-disease studies: a review of current methods. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:869–xc.

-

Luz A, Santatiwongchai B, Pattanaphesaj J, Teerawattananon Y. Identifying priority technical and context-specific issues in improving the conduct, reporting and apply of health economic evaluation in depression- and middle-income countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;xvi:iv.

-

Onukwugha East, McRae J, Kravetz A, Varga S, Khairnar R, Mullins CD. Cost-of-affliction studies: an updated review of electric current methods. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:43–58.

-

Franken 1000, le Polain Thousand, Cleemput I, Koopmanschap Thou. Similarities and differences between v European drug reimbursement systems. Int J Technol Assess Wellness Care. 2012;28:349–57.

-

Welte R, Feenstra T, Jager H, Leidl R. A decision chart for assessing and improving the transferability of economic evaluation results betwixt countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:857–76.

-

Zhao F-L, Xie F, Hu H, Li South-C. Transferability of indirect cost of chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31:501–8.

-

Sullivan SD. The transferability of economical data: a difficult endeavor. Value Health. 2009;12:408.

-

Knies S, Severens JL, Ament AJHA, Evers SMAA. The transferability of valuing lost productivity across jurisdictions. Differences between National Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines. Value Health. 2010;thirteen:519–27.

-

Brodszky Five, Beretzky Z, Baji P, Rencz F, Péntek M, Rotar A, et al. Cost-of-disease studies in nine Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;xx:155–72.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Aida Farha, medical information specialist at the American Academy of Beirut, for her help with the database search and retrieving full-text articles.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to bear this report or prepare this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Jalal Dahham, Rana Rizk, Ingrid Kremer, Silvia M.A.A. Evers, and Mickaël Hiligsmann have no conflicts of involvement that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approving

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Non applicable.

Availability of data and material

All the data supporting the findings of this study (i.due east., search strategy and the information extracted from the studies included in the review) are bachelor within the article and the electronic supplementary cloth.

Lawmaking availability

Not applicative.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the concept and design. JD performed the searches. JD and RR conducted the title and abstract screening. JD, RR, and IK conducted the total-text screening, information extraction, and quality assessment. JD drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed nether a Artistic Commons Attribution-NonCommercial iv.0 International License, which permits any not-commercial utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and bespeak if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this article are included in the commodity'south Artistic Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If cloth is non included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will demand to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dahham, J., Rizk, R., Kremer, I. et al. Economic Brunt of Multiple Sclerosis in Depression- and Middle‐Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics 39, 789–807 (2021). https://doi.org/x.1007/s40273-021-01032-7

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Upshot Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1007/s40273-021-01032-7

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40273-021-01032-7

0 Response to "The Indirect Costs of Multiple Sclerosis Systematic Review and Meta-analysis"

Post a Comment